Staying The Course

NAVIGATOR

Audrey Fraizer

This should come as no surprise: The risk of gaining weight as an emergency dispatcher rises proportionally to how long the person’s been at the job.

Or, at least, that’s the findings in the study “Predictors of Obesity and Physical Health Complaints Among 911 Telecommunicators.”1

And get this: The rate of obesity (53.4 percent) among the 758 people involved in the study was 50 percent greater than the national prevalence rate (34.9 percent), and less than one in five telecommunicators fell into the normal weight category.2

Of course, that’s not something an emergency dispatcher wants to hear, given the dearth of information already available on the topic and a helplessness to do anything about it. As if emergency dispatchers don't have enough demanding their attention.

The profession offers lots of pluses—ability to help people in a crisis and being among the first to hear a baby’s welcome to the world—but it’s also a beehive of stress, triggering unwanted side effects such as backaches and headaches, plus the dreaded emotional eating. Emergency dispatchers aren’t alone here. Experts estimate that 75 percent of consuming large quantities of high-calorie, high-carbohydrate junk food is caused by emotions.3 It’s a coping mechanism and without much concentrated practice, the habit develops into an eating style. You reach for a snack whenever you are bored or stressed and without thinking about what you’re doing.

The irony is that many people caught in the web of emotional eating realize that it’s neither good for their health nor adding to job satisfaction. Yet, how do you make the changes associated with controlling the urge to eat when satisfying cravings other than hunger?

“These are settled habits,” said Susanne Ottendorfer, Medical Director, 144 Notruf Niederoesterreich of Lower Austria. “You have to work on better health every day.”

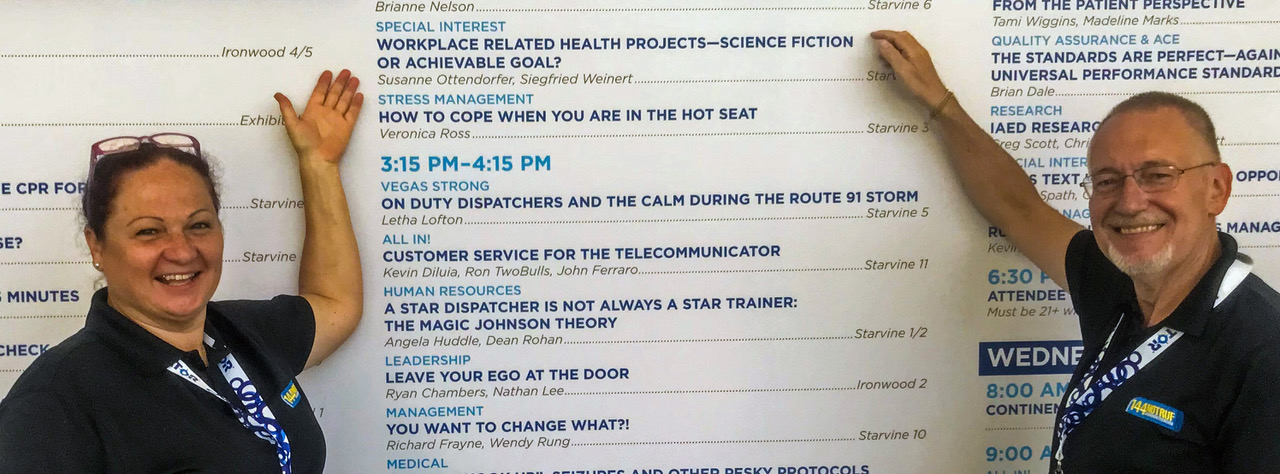

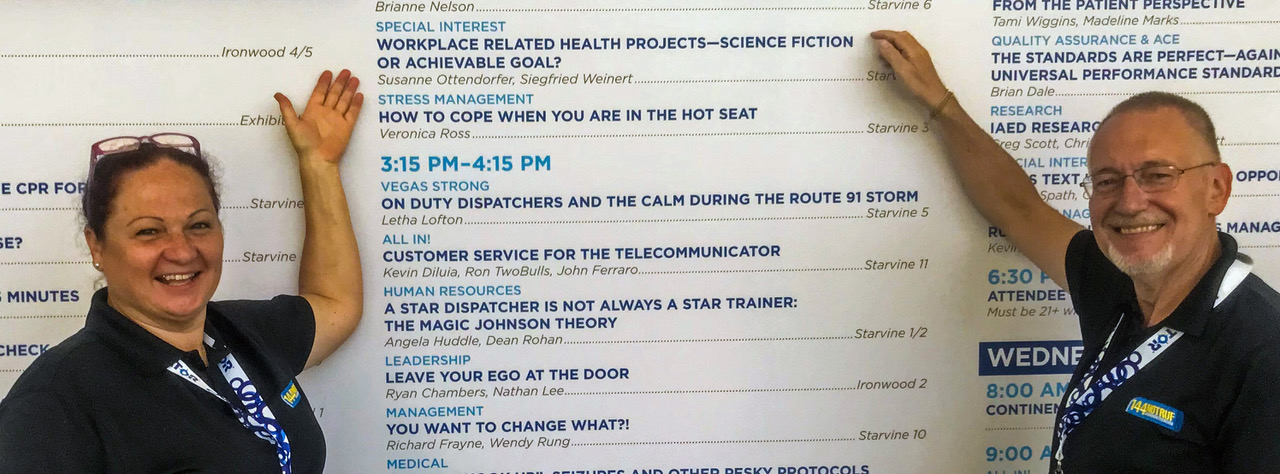

Ottendorfer and Siegfried Weinert, Special Projects Coordinator, 144 Notruf Niederoesterreich of Lower Austria, made their case for healthier habits, and sustaining them, during the NAVIGATOR session “Workplace Related Health Projects—Science Fiction or Achievable Goal“—or to say it straight: From Fat to Fit! According to a study they conducted, 13.9 percent of the 144 Notruf Niederoesterreich calltakers and dispatchers voluntarily completing a 44-question survey perceived their diet as “not healthy”; 55 percent of the respondents gained weight after starting the job and many fell into the obese weight range.

“They’re not happy about it,” Ottendorfer said.

Lack of awareness isn’t central to the problem. Emergency dispatchers know what it takes to promote health. They want healthy selections at the vending machines. They want a fresh fruit basket in the break room. They want memberships to fitness places. They want to avoid soda. They want counseling before stress becomes overwhelming. The ways they knew to achieve their goals, however, aren’t always available or sustainable.

“The personal health promotions they have tried often fail,” Weinert said. “With a lack of support strategies, they relapsed into old habits. And you know: Old habits die hard.”

Weinert, who worked for a workers’ compensation company involved in workplace health promotion, knows why many workplace health promotion projects fail. Big kickoff events motivate employees but drive decreases without further support.

Ottendorfer and Weinert are keen to reinforce fitness goals by turning survey results into positive action. Together with the Lower Austrian health department, they started a “feel good” certification process at Notruf Niederoesterreich.

It continues on incentives already available. For example, the center provides fresh fruit (and it’s free) and promotes coffee, tea, and water (also at no cost) to replace sugary beverages. Now, Weinert and Ottendorfer are also advancing the concept of “health literacy,” an approach that draws on the Ottawa Charter for Health promotion. The document was considered a founding document to promote public health when it was released in 1986 and embraces the World Health Organization (WHO) constitution preamble: Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”4

They’re not out to change the world.

“We want to see people [in the communication center] take control of their fitness and health,” Ottendorfer said.

Ottendorfer and Weinert plan a second survey in 2020 to review progress in achieving healthy goals and the effects on job satisfaction, motivation, efficiency, and quality of work.

For more information on this topic please contact Ottendorfer (susanne.ottendorfer@notrufnoe.at) or Weinert (siegfried.weinert@notrufnoe.at)

Sources

1 Lilly M, London M, Mercer M. “Predictors of Obesity and Physical Complaints Among Telecommunicators.” Safety and Health at Work. 2016; March. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4792921/ (accessed May 14, 2018).

2 See note 1.

3 “Medical Definition of Emotional Eating.” Medicinenet. 2016; May 13. https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=46450 (accessed May 14, 2018).

4 Potvin L, Jones C. “Twenty-five Years after the Ottawa Charter: The Critical Role of Health Promotion for Public Health.” Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2011; July/August. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41995602?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents (accessed May 14, 2018).